»And in his needy shop a tortoise hung, an alligator stuffed and other skins of ill-shaped fishes...«

William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, 1595

»De materia medica« is the title commonly given to the encyclopedia composed by Greek physician Dioscorides in the 1st century A.D. This pharmacopoeia details the pharmaceutical knowledge of that time in the form of numerous systematic monographs. It enjoys renewed attention during the Renaissance, an era characterized by the revival of classical art and literature along with an utter fascination for texts that have been handed down through the centuries. Because people recognize the importance of knowing all options for intervening in the fateful process of disease and healing, Dioscorides’s work is incorporated into the medicinal practices of the medieval monastic communities.

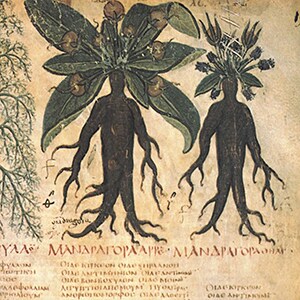

»Materia medica« will become a fixed term for the medicinal resources found in the kingdoms of nature – therapeutically useful materials of plant, animal and mineral origin. Every substance has the potential to be either a medicine or a poison. Like the head of Janus, each drug has a dual nature, the ambivalence of a desired and harmful effect. Deadly nightshade, opium poppy and henbane all contain highly toxic compounds, explaining why they are categorized as »witches’ herbs« for centuries. However, humankind has also always considered it natural to leverage the power of plants. Is their appearance not an indication of their curative benefits? A spectacular example of this approach is mandrake. Known scientifically as Mandragora officinalis, the shape of this »magic root« resembles a human body. Being one of the original functions of apothecaries, the sale of precious active ingredients such as »Balsamum de Mecca« represents a »beneficial and lucrative« therapy. Some substances such as frankincense and myrrh are associated with metaphysical and religious concepts because they are considered to purify and heal body, mind and soul.

Medicinal agents of animal origin are said to have special powers. Due to their poison, for instance, vipers are said to fend off diseases. Ultimately, man is considered the most perfect of all creatures, with preparations made from blood or breast milk viewed as having the greatest efficacy.

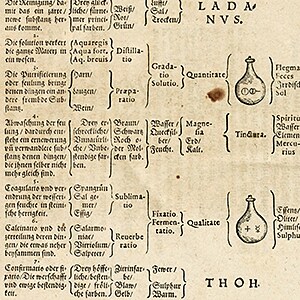

Under the influence of Paracelsus, in the 1520s western pharmaceutical science embarks on a systematic search for the secret powers of inanimate nature. According to natural-philosophical theories, for instance, gold compounds are thought to be life-extending panaceas. Analogous to its power to transmute base metals into precious ones, the »elixir« is thought to have a wondrous effect inmedicine as well. This philosophy gives rise to the highly complex theoretical concept of iatrochemistry.

A glance at a pharmacy in the 17th century with its immense variety of simplicia and composita shows that people will only come to relinquish these ideas reluctantly. The »ars pharmaceutica« will continue to adhere to centuries-old traditions of medicine for a long time to come.

Wealthy pharmacists are passionate collectors of vegetabilia, animalia and mineralia. In the cabinets of curiosities of the Baroque era, blowfish and alligators reflect the macrocosm, acting as symbols of powerful substances. Even if customers only catch a glimpse through the window into the dispensary, the objects serve as a »wondrous« advertisement.

Essential oils obtained through laborious processes are considered to have special qualities. These compounds are attributed special powers to penetrate and heal the body; upon being inhaled, they can transform the power of the »quinta essentia« into a sensual experience through their subtlety.

The »Pharmacopoeia medico-chymica«, written by physician Johann Schröder and first published in 1641, makes clear just how thoroughly ancient and medieval theories and approaches permeate the art of pharmacy. Reprinted multiple times, the work is presumably also used in the company pharmacy.