»[Everything possible must be done to] elevate pharmacyfrom an empirical manual craft to a scientific art…«

Johann Bartholomäus Trommsdorff, 1810

Pharmacists have always understood their craft. They possess extensive knowledge, taking a systematic, often methodical approach to their work. But do theywork in a scientific manner?

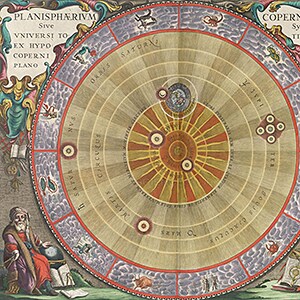

New findings will only be incorporated into the canon of science once they can be explained by this discipline-based system, or at least substantiated by it. The rules governing a scientific system’s internal logic must therefore be as clear and unambiguous as possible. In ancient times, people only apply this method to the physical sciences, the »physikè epistéme« – the »philosophia naturalis«. The term natural science is coined in the 18th century as an equivalent of »philosophia naturalis«. Driven by the search for principles, it emphasizes empiricism, experimentation and formalism.

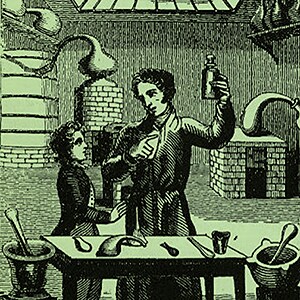

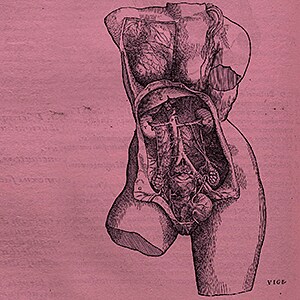

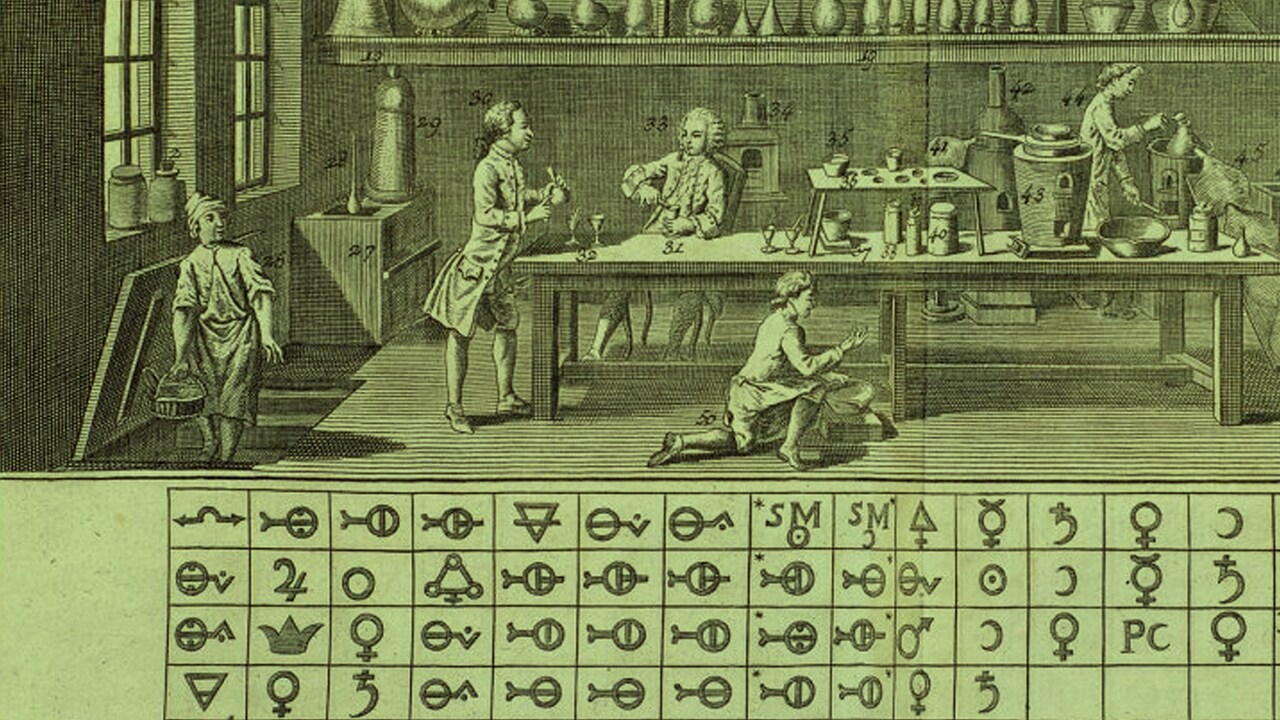

Previously characterized by a rather theoretical approach, chemistry is well suited to this approach. But on what is it based? It is built on the arts of metallurgy, dyeing, and beer brewing, along with the art of medicine preparation, known in Greek as »pharmaceutikè téchne« and in Latin as »ars pharmaceutica«. The groundwork laid by pharmacists helps chemistry gain recognition as a science before their own field is able to benefit from their efforts – the pharmaceutical arts are considered a »mechanical art«.

Yet critically minded pharmacists are still seeking to identify the healing »essence« in medicines. Whether attempting, through distillation, to extract the »quinta essentia« or isolate the »principium somniferum« in opium, the pressure to not only recognize drugs but to understand them acts as a powerful motivator to create knowledge. In this process, the respective intellectual or cultural background alters the manner in which knowledge is generated as well as its nature. Points of view strange to us today are not unscientific simply because they are no longer accepted now. Today’s perspectives would then also be considered unscientific because they too will presumably someday cease to be accepted.

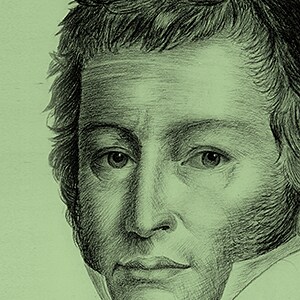

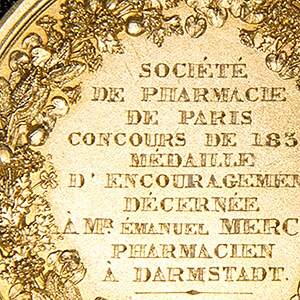

In transforming pharmacy into a science, one fascinating substance will play a major part: opium, a drug that is both respected and feared at the same time. Could it be possible to isolate its positive powers? Friedrich Sertürner discovers morphine in 1805. Yet the scientific community will come to regard this pharmacist’s apprentice with skepticism, if at all, even though his assertions should have shaken up the establishment: »Physicians no longer have to struggle with uncertainty and inexactitude [...]; they will be always able to avail themselves of this substance with equal success.« He assiduously documents his experiments, perceives the whole from individual components. He unites ability and knowledge. And yet it will be another individual who will make morphine »commonly known« – Emanuel Merck.

In Antiquity, the terms »epistéme/scientia/philosophia« stand in direct opposition to »ars/téchne«. According to the mindset that dominates until well into the 19th century, »arts« and »crafts« cannot possibly be »sciences« because they involve the manufacture of artifacts.

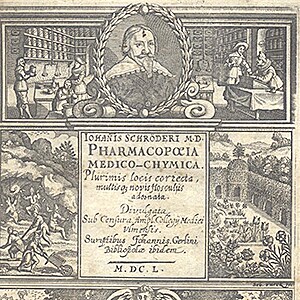

In 1641, physician Johann Schröder deliberately chooses to use the term» pharmacologia« in his pharmacopoeia, a word derived from the examples of »theologia« and »astrologia«. The suffix-logia demonstrates how he already views pharmacy as an academic discipline while also considering it part of the field of medicine.

In addition to his research, Emanuel Merck will make great strides in helping to transform his discipline into a science. He defends hypotheses with poise and debates findings in an efficacious manner; he builds interdisciplinary networks, seizes the opportunities of internationalization, and unites science and business.