»I am going to have a study of the famous coca carried out […]. I received a whole crate full […]. I am adding a few leaves for you along with the cigars.«

Friedrich Wöhler to Justus Liebig, 1859

Initially, most people consider cocaine to be a psychoactive drug. But are there other aspects of the active ingredient derived from the Erythroxylum coca plant – and what does the company have to do with this?

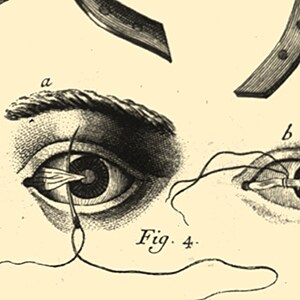

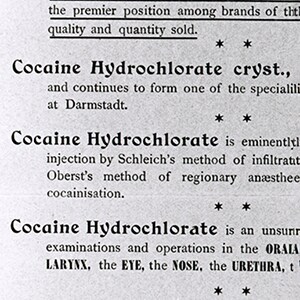

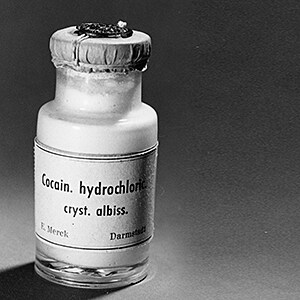

Wöhler, a chemist based in Göttingen, tells the Viennese Academy of Sciences in 1860 that his assistant Albert Niemann has found a »new organic base in coca leaves«, an alkaloid called cocaine. The company immediately launches its own activities – after all, the company has pledged to make the full spectrum of alkaloids available to science. Cocaine is listed at a high price of 16 marks for one dram [3.6 g] and is soon rated the best of its kind. Reports from the research department show the importance of the substance for the company, which will soon be isolated »on a factory scale« from raw material imported from Peru or Java.The idea of wide-scale medical use of the »wonderfully invigorating and performance-enhancing« substance does not come up until 1884: »The agent evidently [captures] the interest of physicians«, the company reports. The Viennese neurophysiologist Sigmund Freud writes: »I intend to send for this agent and […] try it in the treatment of heart disease and weak nerves, in particular to manage the wretched state of morphine withdrawal.« Soon, however, interest shifts to an entirely new use: The ophthalmologist Carl Koller uses cocaine in eye drops for pain relief during surgical procedures, marking the beginning of the development of local anesthetics.

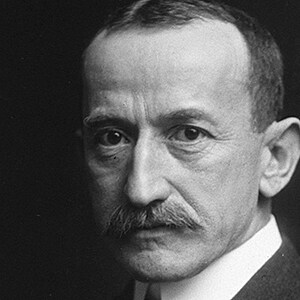

»Although no doubt may prevail that cocaine is a poison,« the company rates it as »one of the most valuable agents in various different branches of medicine«. Two of the young Merck family members, Willy and Carl Emanuel, devote themselves to cocaine research. 1896 sees the beginning of decades of collaboration with the later Nobel laureate Richard Willstätter, who succeeds in elucidating the constitutionand synthesis.

Business records document extensive contacts, for instance to Russia, China, and the United States. Serious competition is rare until 1914, with agreements regulating what soon develops into an international market. Abuse is an increasing problem, however, and tougher legislation is introduced as of 1920. The company works hard on partial synthetic modifications of the molecule to eliminate the addiction potential. As early as 1905, competition emerges in the form of procaine from Hoechst. Psicaine is an initial success. But in 1928, it is stated that »cocaine has retained its position as the most effective local anesthetic«.

Ortiz, a Spanish priest, mentions coca leaves in 1499 as a stimulant used by the native South American population. Monardes, a famous 16th century physician teaching in Seville, recommends coca leaves to fight hunger and fatigue. The first leaves are brought to Europe in 1749 and described in Lamarck’s »Encyclopédie Méthodique Botanique« in 1786.

Carl Koller recalls his experiments with cocaine solutions during eye operations which, before 1884, were performed »without anesthesia of any kind«: »Cocaine stocks amounted to merely a few grams at the time and were provided by Merck in Darmstadt. […] I […] found the cornea and conjunctive membranes to be insensitive.«

Amid efforts to regulate drugs, the International Opium Conference results in the first international convention. Participating states promise to impose strict controls on cocaine production and trafficking. A first draft is agreed upon in 1912. The convention enters into force globally in 1919 as part of the Treaty of Versailles.