»Ecstasy culture […] was the best form of entertainment onthe market, a deployment of technologies – musical, chemicaland computer – to deliver altered states of consciousness...«

Matthew Collin, John Godfrey, Altered State.The Story of Ecstasy Culture and Acid House, 1997

A substance takes the world by storm in the 1990s. MDMA, its scientific abbreviation, achieves huge popularity as »Ecstasy«: The body and mind-altering effects of a white powder provoke wonder and alarm. On another level, scientists keep a very close watch on MDMA. The drug has been used since the late 1970s by psychiatrists in the United States to treat post-traumatic stress disorders unresponsive to any other therapy. The scientific community struggles for transparency and responsible use.

Drug abuse inevitably feeds speculation, not only in the lay press. The assertion »Merck invented Ecstasy!« provokes consternation. What does Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, have to do with it?

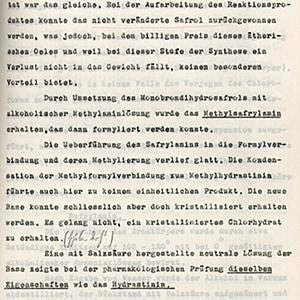

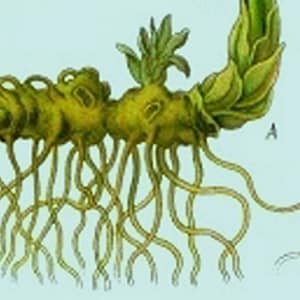

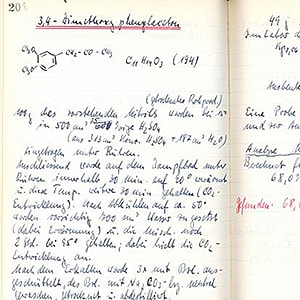

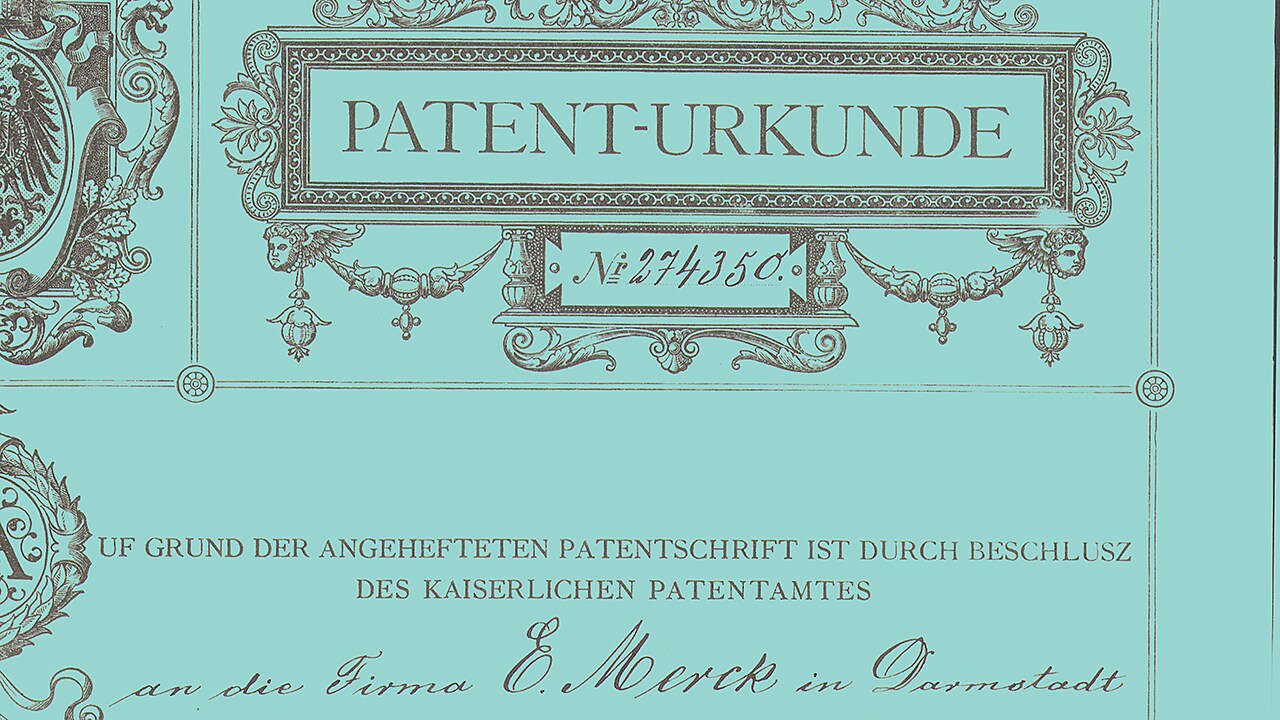

Hydrastinine, a blood clotting agent, is still being laboriously isolated from plants in 1910 when a Hanover Veterinary College researcher offers a way to synthesize it. The company hesitates too long: Bayer, its Leverkusen-based rival, acts fast and brings the important drug to market »with much publicity«. E. Merck, Darmstadt, Germany, has to react. Two patents are filed in 1912. The first is for a process to synthesize key substances, and the second patent, which is based on the first, patents the »procedure for the manufacturing of hydrastinine derivatives«. In retrospect, an intermediate mentioned in the first patent is interesting: »Methylsafrylamin« – or MDMA in today’s nomenclature.

There is no evidence that this compound incites any pharmacological interest whatsoever. On the other hand: MDMA is an interesting molecule for chemical purposes. A researcher takes a second look at the documents in 1927. There is a structural similarity to »ephetonin«, a synthetic ephedrine the company is looking into. Would it be wise to take another look at the »historic« substance? Having initiated simple pharmacological tests, he sees sympathetic nervous system effects such as increased cardiac and metabolic activity – and high toxicity. There is no way now to reconstruct the methods he used. Experiments on isolated organs, perhaps?

It is certain that safrylmethylamine is only tested in a preclinical setting. It is certain that there is no knowledge of any psychoactive effects. Work on the compound is again terminated. In the 1950s, the U.S. army is looking into potentially mind-enhancing substances. Scientists now know more about structure-effect relationships, and MDMA’s basic structure again comes under scrutiny – and again there is no convincing reason to take things further.

The first paper on the psychoactive effects of MDMA, authored by Alexander Schulgin, is not published until 1978 in the United States – when the company has ceased to have any connection to the substance.

Checkered drug career: MDMA, an uninteresting intermediate from the synthesis of a blood-clotting medicine, later taken up by psychiatrists, achieves dubious popularity on the 1980s rave scene because of its anxiolytic, euphorigenic and mind-altering effects.

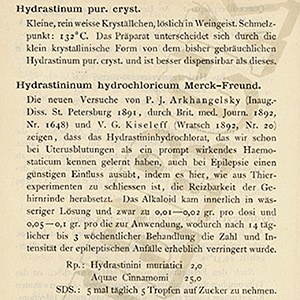

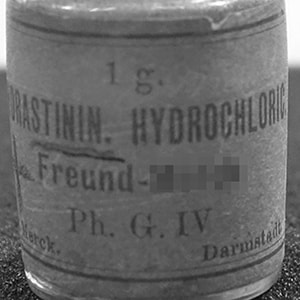

Pharmacists show special interest early on in hydrastinine, a naturally occurring alkaloid with promise in controlling abnormal bleeding. For many years, the company harvests it from the root of Hydrastis canadensis, but this medicinal plant becomes increasingly scarce and costly; cultivation efforts fail.

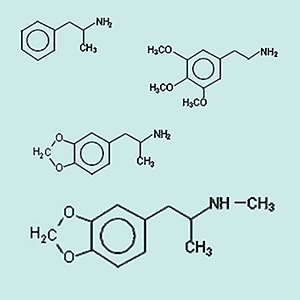

MDMA belongs to a class of stimulants chemically derived from amphetamine but with some similarities to mescaline. This 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine goes by many synonyms in the literature, which does not make it any easier to unearth the true facts about its origins – and the role played by Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany.