»How could a rigid, well-ordered system of molecules, as which we imagine a crystal, acquire similar external and internal characteristics of motion such as those we use to describe liquids.«

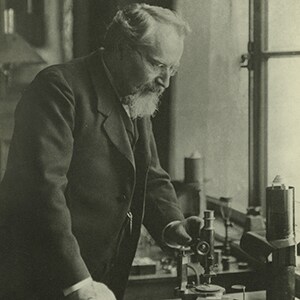

Otto Lehmann, 1889

Otto Lehmann, a physicist who began investigating the behavior of crystals and phase transitions back in the 1870s, publishes the results of intensive research in 1889. His statements are not only bold, but revolutionary, calling a centuries-old dogma into question. It is considered a generally accepted fact that three states of matter exist: solid, liquid and gas. However, the phenomena described for the first time by Lehmann fall outside the confines of this system. Another state ofmatter is said to exist.

The impetus for Lehmann’s investigations comes from Friedrich Reinitzer, who works at the Institute of Plant Physiology in Prague. While analyzing the ingredients of carrots, he focuses his interest on sterols and cholesterol. However, during his research he is irritated by »peculiar phenomena«: Both acetate and benzoate exhibit a viscous, cloudy »mass« for a long time when heated, long before they become a clear melt.

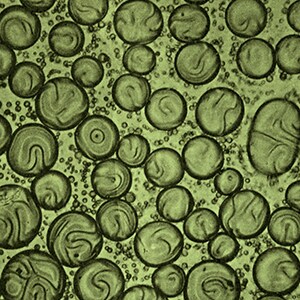

Letters and samples are exchanged. For these substances, there must actually be another phase between the solid and liquid state that changes the direction of polarized light. Using a self-constructed, heatable microscope, Lehmann observes the behavior of these substances under the influence of heat, thus creating theoretical and experimental prerequisites for proving that there is a new state of matter that has never been described before.

Controversial discussions ensue in the scientific world. In 1905, the dispute reaches a climax when Gustav Tammann, a chemist working at the University of Göttingen declares: »Soft crystals undoubtedly exist, for my part flowing crystals are also supposed to exist, but liquid crystals? Never!«

Lehmann then sends a letter to Darmstadt. E. Merck, Darmstadt, Germany, is known for »supporting scientific research as far as possible«, also and especially in fields whose value cannot be estimated at first glance. The substances that are so complex to produce do in fact contribute substantially to guiding the dispute into a constructive direction. In the 1920s, the theory of liquid crystals is recognized – a triumph of collaboration between different research personalities and disciplines, university and industry.

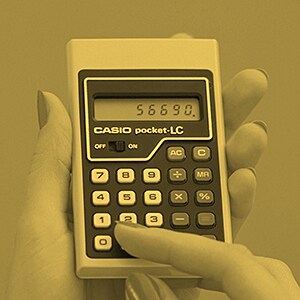

What can be done with these findings? There are no ideas about possible technical applications. A long slumber begins. Yet at the end of the 1960s, the company brings these exciting substances back to life. The presentation of the »German Future Prize« in 2003 for this achievement is only one indication of the brilliant development of this research field.

In order to be able to investigate liquid crystals, Otto Lehmann has to modify his laboratory equipment. He mounts small gas burners on a microscope together with a stage to observe the behavior of the substances at different temperatures. Samples that he receives from the company are also investigated.

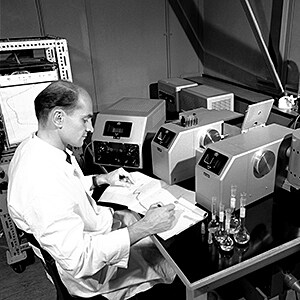

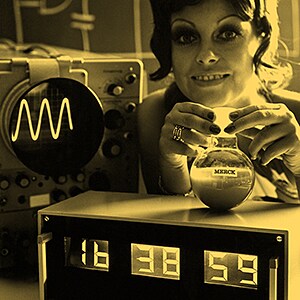

At a meeting in late 1966, a chemist at E. Merck, Darmstadt, Germany, presents a technical article on possible technical applications of liquid crystals. It was decided to also look into possible applications of liquid crystalline substances. Lehmann’s work experiences a renaissance and research resumes.

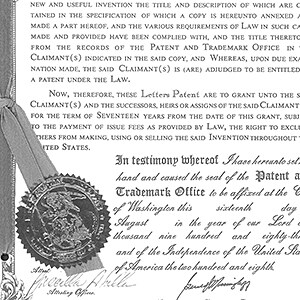

Research and development work at Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, on further application possibilities is steadily deepened, patented and recognized. The idea of a flat screen hanging like a picture on a wall starts to take shape. A laboratory curiosity becomes a great economic success.