»I would appreciate it very much if you would look more closely into this matter and the feasibility of using a fuel of this kind in your country […]. The whole matter may fail due to Prohibition.«

Karl Merck to George W. Merck, March 25, 1925

The 1921 company image film shows many forms of movement and propulsionon the site premises: wheeled vehicles moved by muscle power, horse-drawn vehicles, gasoline-fueled trucks and steam locomotives. Raw materials must be brought to the production plants, finished products delivered all over the world. It is easy to see how rush hours can occur.

A few years later, a new vehicle adds to the volume of traffic at the site when electrical carts are purchased. »You can no longer imagine the old snail’s-pace handcarts, which were once common, in our fast-paced modern times.« Only 15 years after their introduction, the electrical vehicles have changed people’s sense of time.

Very few people have cars. In the latter half of the 1920s, fuel tanks are filled not only with gasoline and benzene, but also potatoes and turnips. Processed into alcohol, and with the water content removed, agricultural produce becomes a fuel additive. The company plays a key role in developing the required process. Electric vehicles are also already in existence. In the 1910s, Louis Merck owns such a vehicle. When the battery is fully charged, it has a range of 60 to 80 km.

The streetcar has been running since the site moved to Frankfurter Strasse, initially on steam, from the mid-1920s on electricity. In 1927, however, a report notes that the »employees living in Darmstadt are not […] reimbursed for streetcar expenses«. By 1930, 163 company employees had subscribed for a weekly ticket.

Bicycles become a widespread luxury in the 1920s. The number of bicycles seen in the film is modest, but it jumps sharply by the end of the decade. In 1929, parking areas for roughly 850 bicycles are planned for the site’s southern boundary and roughly 500 for the northern boundary. The company supports the spread of this new form of mobility through affordable purchase prices and wage advances. Many people, however, still simply walked. At the start of the 20th century, trips of up to four hours were still a part of daily life for some workers, many of whom came from villages in the Odenwald.

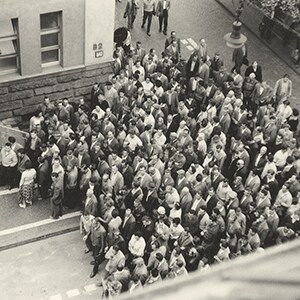

The end of the working day in 1921: Workers and employees stream out of the gate on foot, several bicycles can be seen in the crowd, an automobile drives across the scene. It is rush hour. Yet with the advent of flexible working hours at the end of the 20th century, this phenomenon is no longer attributable to one period of the day.

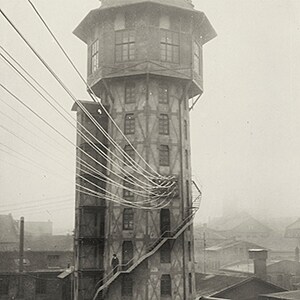

The company’s own coal-fired power plants provide the energy required by the site. An extensive grid transmits power from the plants to the individual machines. In 1895/96, at the old site, hydropower is also already in use. Through the installation of Pelton turbines, the kinetic energy of the falling water is harnessed to power machinery.

The light railway is the first choice for transports of all kinds on the site premises, not only in the 1960s. The small carts are seldom this empty. An employee in the 1920s uses a scooter to traverse the extensive packaging plants. Since 1924, electrical carts have also been in use at the site.

Fixed working hours regularly lead to high volumes of traffic – whether in 1953 or in 1963. Even in winter 1976, despite the icy and slippery roads, most employees drive and use the parking lot. The employee newspaper notes: »The streetcars, which were punctual, did not skid, and operated free of risk, remained below capacity, like on other days.«